Travels through the heart of Guatemala, from Lake Atitlan to the Mayan highlands

TIKAL NATIONAL PARK, Guatemala — Edgar is getting on my nerves.

I am hiking through the lush rainforest of northern Guatemala with a friend, Colleen, and our guide, Edgar Diaz. Noise and movement follow our every step, for the tall hardwood trees are filled with howler monkeys, macaws and clamoring urracas, whose nickname, the alarm bird of the jungle, fits all too well.

We pass by a ceiba, a tree sacred to the ancient Maya; hundreds of inch-long spikes jut from its slender trunk like a giant thorned rose. I ask about the jaguars and pumas, said to prowl deep in the shadows, but Edgar wants to talk roots.

He plucks a few delicate leaves from a tree — the leaves of a spice, he tells us — and hands them to us. The woods are heavy with its familiar scent. Seven times now we have chewed the root; still, we can’t identify it. This, naturally, delights Edgar.

“Arrowroot? Ginger? Anise!” I venture.

“No, no, no,” Edgar says.

After a time — Edgar perilously close to his final game of Name That Spice — he relents. Allspice. (Of course!)

Guatemala is filled with such small moments of discovery.

What’s surprising is that so few Americans have discovered Guatemala, Central America’s most populous and diverse nation. Tourism exploded in the past year: The Guatemala Tourist Commission estimates 450,000 tourists visited last year, up 28 percent from two years before. Yet visitors come chiefly from western Europe; only a quarter are from the United States.

Travelers come for many reasons: for the Mayan ruins that rise out of ancient rainforests; for the astounding volcanoes that shoot up from rich terraced hills; for the postcard-perfect colonial settlements, the fringy bohemian outposts, the wildly colorful Indian marketplaces.

What will most likely stay with the visitor, however, are impressions of the people, for the Guatemantecos have fashioned a multiethnic society that is a remarkable fusion of cultures.

Fifty-five percent of the population are native Indians, direct descendants of the Maya, whose ancient civilization stretched from Honduras to Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

The Indians, or indigenas, speak their own languages, wear exquisite hand-woven costumes and live in the rural highlands. The ladinos, who run the government and control the economy, speak Spanish, wear Western dress and live in the capital and coastal lowlands. (The distinction is cultural, not racial, for many ladinos are full-blooded Amerindians.

Be forewarned, this is no Acapulco, no weekend jaunt for the pool-and-Margarita set. But a trip here last spring by a couple of visitors who speak little Spanish showed that getting around Guatemala is no more formidable than traveling in other foreign lands — New York, for instance.

The basic traveler’s circuit of Guatemala can be accomplished in a week, but it’s better savored in two. Either way, any visitor’s itinerary should include four not-to-be-missed destinations: the ancient Mayan ruins at Tikal; the colonial city of Antigua; the resort village of Panajachel at Lake Atitlan; and the Indian marketplace at Chichicastenango.

Those pressed for time might want to skip the congested capital of Guatemala City altogether, for there are far richer experiences awaiting elsewhere.

Tikal: ‘Center of Echoes’

Hidden for centuries beneath the jungles of northern Guatemala lie the remnants of the New World’s cultural center. Tikal, the premier city of the ancient Mayan civilization, flourished from a few hundred years before Christ to 900 A.D.

The ruins were discovered in 1848; excavation and restoration took place from 1956 to 1969. But it has been only in the past 10 years or so that visitors have been able to reach the site with relative ease.

Tikal is peppered with thousands of structures over 12 square miles: stepped pyramids containing underground burial chambers; stone altars for ritual human sacrifice; and chiseled tablets called stelae, which the Maya used to keep an accurate calendar and precise chronicle of the heavens’ movements.

Our guide, Edgar, leads us past carved tablets depicting the Maya’s symbol of wisdom: the serpent. “This did not go over so well with the Christian missionaries,” Diaz observes. Farther along, we pass a courtyard where Mayan ballplayers in padded leg gear once competed in a sport somewhat akin to basketball. (A rather unsettling twist is that the captain of the winning team would have his head cut off immediately following the game.)

We continue on to the Plaza Mayor, or Great Plaza, said to be the Maya’s most impressive visual legacy. One pyramid, the Temple of the Giant Jaguar, rises 145 feet high at the eastern end. A second pyramid, the Temple of Masks, rises 127 feet to the west.

The temples served as astrological observatories as well as sacred places for ceremonial sacrifices. The limestone monuments are now stone-gray, but during Mayan times they were the color of blood.

“Tikal,” Edgar says darkly, “means ‘center of echoes.’ ”

Mulling this, Colleen and I climb the decaying stairway leading to the chamber atop the jaguar temple. From there, one can take in the sprawling acropolis and imagine a time when it was alive with activity. Archaeologists still don’t know what led the Maya to abandon Tikal and other major cities around 900 A.D.

After a time, we head back to the Jungle Lodge, at the center of the 222-square-mile national park that encompasses the ruins. We decide to stay the night — an experience that proves richly rewarding. We wake up to the animal sounds of the jungle, and listen to the tropical rainstorm that beats like kettle drums on our thatched roof. We then set out for a second day of taking in the ruins at an unhurried pace.

Antigua

From Guatemala City, it’s only a 40-minute drive up the Pan-American Highway to Antigua.

The village is a page out of Guatemala’s colonial past. We stroll on 400-year-old cobblestone streets, past dozens of low-slung sandstone buildings washed in light. To the south, a mist-draped volcano, Agua, looms over the town, rising 12,356 feet above sea level.

Antigua, at its height, was said to be the most beautiful city in Latin America. The third Spanish capital in the New World after Mexico City and Lima, it flourished as a center of culture and commerce from 1543 to 1773, when an earthquake leveled the city.

Many of the colonial-era structures destroyed in the quake were rebuilt in the original baroque style. Today, Antigua is a living museum — a city of churches, monasteries and tile-roofed estates both restored and in decay.

Most of the action takes place in the center of town at the main square. Long ago there were bullfights and public hangings here; now the square is a place of gardens, fountains and peddlers.

At El Jardin, a small lunch spot on the west side of the square, we meet Edgar, a young, ruddy-faced Guatemalan studying English at a local school. An Indian woman approaches our table, dangles a necklace of jade and offers it for 100 quetzales, about $40. “Te gusta? Es muy precioso.”

Edgar takes the strand and launches into a consumer-awareness number. “A lot of people get ripped off buying fake stones,” he says, setting down his Gallo beer. He turns the necklace in his hand, looking for traces of green dust inside the green hole where the stone is strung.

“Yes, looks real,” he says, “but let’s be sure.” He scratches the stone against his beer bottle, slicing the glass. “That’s real, all right. Jade is harder than marble. Marble is softer; it won’t cut glass.”

After lunch, we wander across the square to the Cathedral of Santiago, first built in 1543. Only its magnificent outer shell remains; inside is a vast array of fallen arches broken columns and collapsed walls.

Before the day is out we hit upon Casa de Artes, an art shop with intricate textile weavings, handicrafts and pottery; the Jade Factory and Showroom, where newly quarried jade is carved; el mercado, where the stalls overflow with mangoes, papayas and bananas; and Musea Kojoa, a private museum you won’t find on the tourist maps (it’s five blocks west of the square), which features ancient Mayan instruments, including the precursor of the marimba.

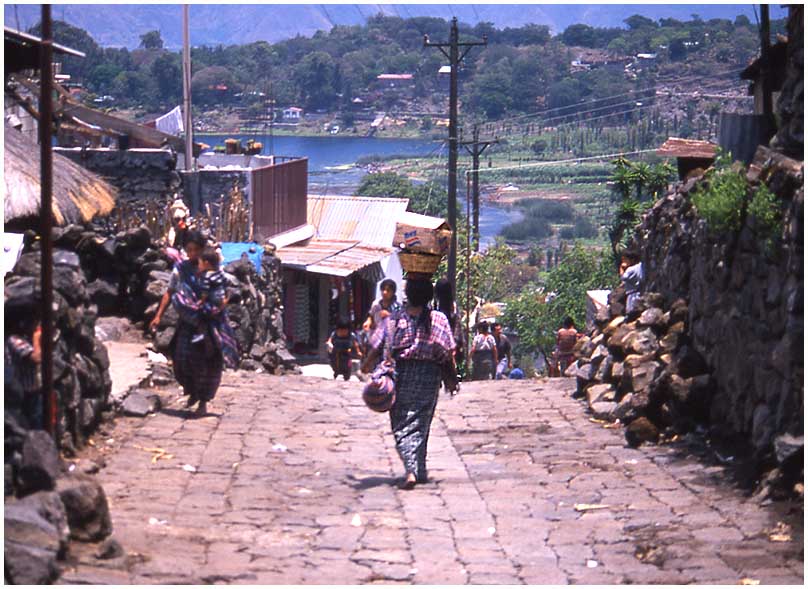

A woman carries a basket atop her head in Santiago Atitlan.

Lake Atitlan

Nestled in the hills three hours northwest of Guatemala City, Lake Atitlan is a mile-high wonder of startlingly blue, wind-tossed waters set against a backdrop of three 10,000-foot volcanoes — Toliman, Atitlan and San Pedro — jabbing at the southern sky.

Author Aldous Huxley once called it the most beautiful lake in the world.

Lining its shores are a dozen Indian villages where life and customs have changed little over the centuries. But there is one village, the largest on the lake, where time has stood still only since 1968.

Panajachel (Ponna-ha-SHELL), a town of 3,400 on the northeastern shore, is something of a haven for bohemian types from Santa Monica to Stockholm.

The scene is part Woodstock, part Casablanca. Native Guatemalans mix easily with the hundreds of time-warp wanderers from California, Canada, Sweden and France who flock here each winter to soak up the sun and perfect the art of living on $5 a day.

We pass juice bars, mom-and-pop tiendas, pool halls and burger shops, pressed against one another in non-descript adobe buildings along the main drag (it’s Calle Principal, but don’t look for any street signs, there are none in Panajachel). On Calle Santander, past designer boutiques and tipico shops selling folk art, we get our bearings at Al Chisme Cafe, a sort of gringo central for the backgammon and cappuccino set.

We quickly head back to the street. Here is where one finds the genuine Panajachel — in the dawn-to-dusk bazaars at roadside, where locals peddle intricate textiles, jade trinkets and finger-woven “friendship bracelets” called pulseras. Colleen buys a handful for less than 50 cents each, some as gifts for her nieces, others for friends in the U.S. sanctuary movement who prize them as politically correct.

The next morning we pay the $2 fare and take the ferry across the lake to the Indian village of Santiago Atitlan, whose residents descended from the Tzutuhil people. Residents of most of the other small towns around the lake are descendants of the Cakchiquel nation.

A dozen young girls in native garb, perhaps 10 years old, descend on our party to press their goods: trinkets, scarves, belts and fruits.

We walk the rutted streets to the town square, where tourists hunt for bargains, bartering with ladino and Indian merchants. The poverty is wrenching here, and so we buy but do not haggle.

Still, the indigenas and their exquisite garments are captivating and I am glad we took the ferry.

Chichicastenango

On the two-hour trip north to Chichicastenango, on roads that wind through green terraced hills, there is nothing like hearing Madonna on the car radio to make one long for the pre-global village days.

Chichicastenango, this nation’s most famous Indian city, is actually home to about 1,000 ladinos, but each Sunday and Thursday upwards of 10,000 Indian vendors pour into the central plaza to sell their goods.

Overnight, a tent city springs up in front of the 400-year-old Church of Santo Tomas. Scores of canvas-covered stalls display hand-carved masks and figurines, hand-woven fabrics and clothing, handmade tablecloths and napkins, handbags, ponchos and stuffed toys.

At one stall, after some negotiating, I buy an elaborately embroidered tablecloth from a 70-year-old indigena woman; a stereotype or two is shattered when she whips out a pocket calculator.

Here, as elsewhere in the rural highlands, the diversity of native costume is astounding: More than 200 villages have their own distinctive style of dress — a hummingbird motif, for example — and each individual adds a unique variation to the theme.

The women, especially, adhere to custom, wearing their huipiles (blouses), cortes (skirts) and fajas (sashes). Some of the men wear the traditional short-waisted jackets, knee breeches of black cloth, woven sashes and embroidered kerchiefs around their heads.

Lunch in the plaza is an explosion of sights and sounds. Smoke pours from kettles and clay pots, dogs run underfoot, women dish out soup while their daughters pat down corn tortillas.

Two girls, perhaps 12, argue over who will get to serve tortillas to a handsome boy. The meal — chicken, rice, soup, beans, carrots and a Coke — comes to three quetzales: 65 cents. We leave a large tip.

We return to our hotel, the Mayan Inn. There, the desk clerk tells us, as others have told us during our visit, that Guatemalans are exceptionally proud of their Mayan heritage. Raising a 20-quetzal bill to the air, he points to the Mayan symbols on the national currency.

“You see?” he says. “Here is the Mayan figure for 20. Here is Yum Kax, the Mayan corn god, holding our most important crop. And here is Tecun Uman, our national hero. He was a Mayan leader who fought the Conquistadors, winning many battles. So you see why we are proud?”

Guatemala resources

Last updated April 11, 2002

Getting there and around: American Airlines, United and Continental are among the airlines serving Guatemala. Guatemala now has a passport requirement instead of a tourist card. To get around the country on land, public transportation is challenging and time-consuming; a rental car is recommended but pricey at about $250 a week.

Political situation: For Guatemalans, freedom of speech and movement increased dramatically with the democratic election of a president in 1985. An ambitious peace accord between the government and rebels was signed on Sept. 19, 1996, and has been honored by both sides. Although Guatemala is no longer plagued by the instability of years past, visitors are advised not to flaunt their relative wealth and to take sensible precautions when traveling to remote areas.

Demographics: With 10 million people living in a land roughly the size of Ohio, Guatemala is Central America’s most populous nation and third largest in area. It is the only country in the region largely Indian in culture.

Money: The monetary unit is the quetzal. Prices are generally one-half to one-third what one would pay in the U.S.

Season: High season for tourism is December to March, when the weather is warm and dry.

Food: Guatemala is not renowned for its cuisine. A typical meal consists of black beans, rice, tortillas and beef or chicken. Visitors are advised to avoid water that has not been boiled or bottled and to avoid fruit and vegetables that are not peeled or cooked.

Language: Most hotels and shops catering to tourists have a staff member who speaks English. Elsewhere, only Spanish and indigenous languages are heard. Guatemalans are renowned for their patience with those whose knowledge of Spanish is limited.

Lodging: Advance reservations are suggested during the peak season. The Inguat (national tourist commission) at the Guatemala City airport and in the larger cities can assist travelers with lists of hotels and rates.

In Tikal, the Jungle Lodge, Jaguar Inn and Tikal Inn offer spare but clean rooms and home-cooked meals. (Several small carriers make the hourlong flight from Guatemala City to nearby Santa Elena Airport daily at 7:15 a.m., returning at 4 p.m.; the fare is about $100.)

In Antigua, the Posasa Don Rodrigo ($40 a night) and the Hotel Aurora are top-flight colonial gems with lovely courtyard terraces.

In Panajachel one can find a comfortable room at a mid-range hotel such as the Regis for $17, while top-of-the-line accommodations at the lakeside Hotel Atitlan go for $52.

Chichicastenango is home to two of Guatemala’s most elaborate hotels. The Mayan Inn, originally a colonial estate, has a homey feel, rooms filled with antiques, and a marimba player in traditional garb performing in the gardens ($53 a night). The newer Hotel Santo Tomas features a courtyard with white fountains and lush foliage ($49 a night).

Tourism books: Guatemala Guide by Paul Glassman (Passport Press) and Fodor’s Guide to Central America (Fodor’s Guides) contain detailed information on hotels, sightseeing, history, culture and more.

More information: Maps and brochures are available from the Guatemala Tourist Commission, 1-888-464-8281, or by e-mail at [email protected].

Online resources

• Guatemala travel: an official site of the country’s tourism bureau

• Guatemalaweb: Wide-ranging listings of everything from hotels to market days

• Lake Atitlan: Photos and text of the breathtaking lake

• Guatemala travel: A nice roundup by Britain’s Guardian Unlimited

• Maya: The history, traditions and architecture of the Mayan people

• Stories: Mayan storytellers’ tales handed down from generation to generation

• Istmania: A good portal for travelers to Central America (in Spanish)

Guatemala Photo Gallery

Guatemala Photo Gallery

Chichicastenango:

___________________________________________________________________

Santiago Atitlan:

_________________________________________________________________

Tikal:

___________________________________________________________________

___________________________________________________________

Antigua:

Click to enlarge

_______________________________

WOW just what I was searching for. Came here by searching for hertz car hire in sweden