Welcome to journalism’s newest ethical nightmare: digital enhancement

This article appeared in the Washington Journalism Review, the Boston Globe and the Sacramento Bee in 1988-89.

Afew years ago I wandered into one of those seminars touting the wonders that digital technological would someday bring to photography. Up on the screen, a surreal slide show was in progress: Joan Collins was sitting provocatively on President Reagan’s lap. Click. Joan was now perching, elflike, on the president’s shoulder. Click. Reagan now had a third eye. Click. Now he was bald. Click. And on it went.

The man from Scitex, one of the high-tech outfits that makes these machines, was saying that computers could now alter the content of photographs in virtually any way. It’s all done electronically, with no trace of tampering.

The audience, clearly dazzled, tossed off a dozen or so questions about whether the machines could do this or that. Finally, a hand shot up. “Nobody’s said a word about the potential for abuse here. What about the ethics of all this?”

The reply came: “That’s up to you.”

Thanks, Dr. Science. And welcome to journalism’s newest ethical nightmare: photographs that lie.

In the past few years, this razzle-dazzle gadgetry has been wheeled out of the seminar rooms and into the newsrooms of many of the nation’s largest magazines, newspapers and book publishing houses.

Television, too, has begun to use the same exotic digital artistry that was once confined to special-effects movie studios. That has led some critics to wonder whether TV news producers might be tempted someday to “simulate” news events, using file footage and a computer.

Digital technology’s impact will be no less dramatic in other areas.

Within a decade, hand-held digital cameras — using a microchip instead of film — will be on the market. Presumably, that will allow people to “edit” the contents of their photos. Soon you’ll be able to remove your mother-in-law from that otherwise perfect vacation snapshot.

In the cinema, some experts are predicting the day when long-dead movie stars will be reanimated and cast in new films. “In 10 years we will be able to bring Clark Gable back and put him in a new show,” John D. Goodell, a consultant on computer graphics, told The New York Times.

Beyond such fanciful applications of digital technology, Goodell raised a dark scenario: Consider what might happen if the Soviet KGB or a terrorist group used such technology to broadcast a bogus TV news bulletin about a natural disaster or an impending nuclear attack — delivered by a synthetic Dan Rather.

While an assault by Islamic Jihad on our airwaves is hardly a worrisome prospect for many years to come, there’s a revolution already taking place on the pages of major news publication. And that has plenty of people worried.

Consider:

• Through electronic retouching, National Geographic slightly moved one of the great pyramids at Giza to fit the shape of its vertical cover a few years ago.

• An editor at the Asbury Park Press, the third-largest newspaper in New Jersey, removed a man from the middle of a news photo and filled in the space by “cloning” part of an adjoining wall. The incident prompted the paper to issue a policy prohibiting electronic tampering of news photos.

• The Orange County Register, which won a Pulitzer Prize for its photo coverage of the 1984 Summer Olympics, changed the color of the sky in every one of its outdoor Olympics photos to a smog-free shade of blue.

• The editors of the just-released book A Day in the Life of California used Scitex to alter the cover jacket: A surfboard was moved electronically, the sky was replaced in its entirety, and so on. Inside, dozens of spectacular photos of California and its people were deemed unworthy of the cover in their unaltered condition. “I don’t know if it’s right or wrong,” says co-director David Cohen. “All I know is it sells the book better.”

• Magazines such as Time have combined images of different people photographed at different times, resulting in composites that give the false appearance of a single cover shot.

• In August The Bee’s Automotive section received in the mail a color transparency showing the 1989 Mitsubishi Montero against a glowing orange sky. A spokeswoman for the auto manufacturer, contacted by phone, said, “To tell the truth, we replaced that sky. The original had a smoggy sky, so we took a stock photo and substituted a much prettier sky.” The altered photo was not used.

Are photos still evidence of anything?

Faster than you can say “visual credibility gap,” the 1980s are becoming the last decade in which photos can be considered evidence of anything.

“The photograph as we know it, as a record of fact, may no longer exist in three or four years,” warns George Wedding, The Sacramento Bee’s director of photography.

Jack Corn, director of photography for the Chicago Tribune, one of the first papers to buy a Scitex system, says: “People used to be able to look at photographs as depictions of reality. Now, that’s being lost. I think what’s happening is just morally, ethically wrong.”

The full implications of digital technology are just beginning to be realized: Will photos be admissible in a court of law if tampering cannot be detected? Can newspapers trust the truthfulness of any photo whose authenticity cannot be verified?

What if a photo turned up tomorrow of Kitty Dukakis burning the American flag as a student in the ’60s — should a paper print it? As the price of these machines comes down, what happens when a grocery-store tabloid gets hold of one?

In television, too, the potential for abuse is great.

Professor Don E. Tomlinson of Texas A&M University, writing in the Journal of Mass Media Ethics, sees the day when news producers try to “re-create” news events that they failed to capture on camera — say, the Soviets’ downing of Korean airliner flight 007. Aired on the nightly newscast, such a simulation would leave viewers confused about whether they’re watching the real thing.

Tomlinson goes so far as to suggest that an unscrupulous TV journalist might use digital technology to fabricate a story entirely because of ratings pressure, a desire for career advancement or simply to jazz up the news on a slow day. A shark lurking near a populated beach, for example, could be manufactured with digital retouching.

As far as is known, such a blatant breach of ethics has not occurred in any TV news department. The only incident of the sort came in 1983 when ABC electronically retouched the still photos of the leading racers in the Indianapolis 500 by erasing the logos of corporate sponsors from their headgear.

Digital machinations on television may pose the greatest threat to the credibility of visual images in the long run. But it’s the print media where the war is being waged today.

“People don’t realize how much alteration is going on,” observes Mike Morse of the National Press Photographers Association. “When you’re looking through that Redbook or Mademoiselle or Sports Illustrated tomorrow, there’s a good chance somebody has done something to that picture.”

Where do you draw the line?

Ironically, large publications are snapping up these systems, at $300,000 to $2 million apiece, not for the ability to alter images but for economic reasons. With digital equipment, pictures can be displayed, altered, transmitted to remote printing plants by satellite and published without ever seeing photographic paper, much less a darkroom.

Publishers may love digital equipment for its cost savings, but editors and art directors find it seductive for other reasons. At the stroke of a few keys, the machine operator has the power to “improve” a photo or manufacture a composite photo from two images.

Rolling Stone magazine, for example, used a digital computer to “erase” a pistol and holster slung over the arm of “Miami Vice” star Don Johnson after he posed for a 1985 cover shot. Editor Jann Wenner, an ardent foe of handguns, ordered the change; using a computer saved the time and expense of having the cover reshot.

Clearly, the technology is here to stay. And so the question becomes: Where do you draw the line?

It’s a question that’s always been at the heart of news photography. Pictures have been staged since the 1850s; retouching photos by hand was once commonplace in many newsrooms; and photographers can change the composition of a print in the darkroom. Over the years, ethical standards have tightened. Today, retouching a news photo is forbidden at most newspapers, and faking a photograph is grounds for dismissal.

But ethical standards may have slipped in one key area: making sure the reader recognizes the difference between real and artifical photos.

The distinction is critical. People expect certain kinds of photos to represent reality. In the trade, these pictures are called documentary photos because they strive to portray real events and real people in true-to-life settings. You’ll find them every day in the news pages.

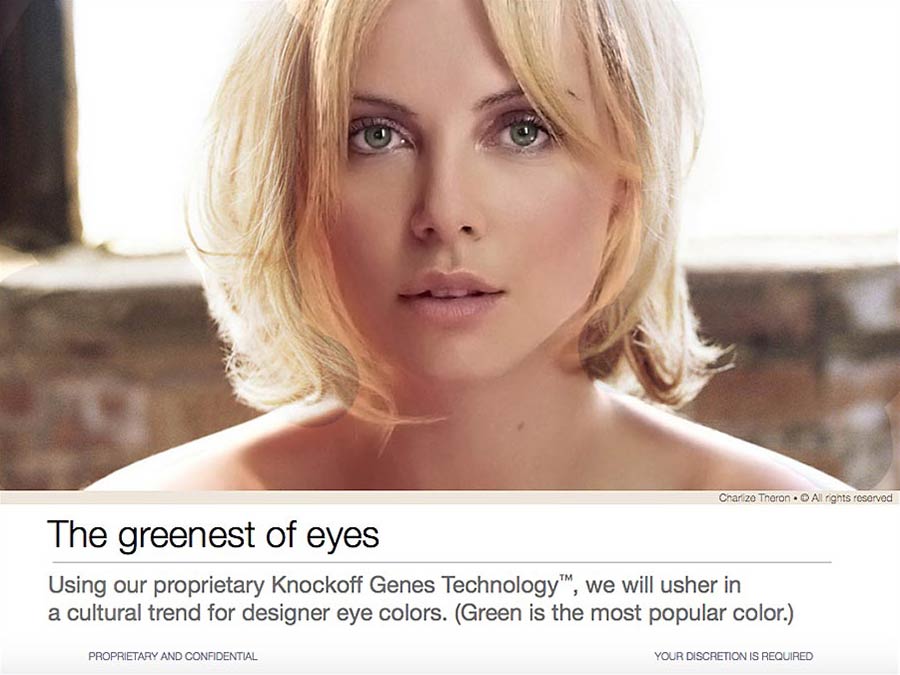

But there are other kinds of pictures, far fewer in number, that do not aim to depict reality. These conceptual photos, or “photo illustrations,” are created often in the studio, and now in computers with the purpose of symbolizing a concept or evoking a mood.

Conceptual photos, such as an art-directed studio shot of a ballet dancer or fashion model or truffle, are more akin to a painting than to the gritty, hard-edged realism of photojournalism. And because the shot was artificially set up in the first place, it’s OK to fine-tune the image to give it more impact.

That’s the conventional wisdom, at any rate.

Blurring the lines

Editors assume that readers are savvy enough to tell the difference between documentary and conceptual photos. But what’s happening, many observers fear, is that digital computers are blurring the distinction between the two styles.

Readers are coming across more and more photos that appear authentic on first glance; when readers look closer and see that the image has been fabricated, they may mistrust the integrity of all pictures on the page.

“People believe in news photographs. They have more inherent trust in what they see than what they read,” says Ken Kobre, head of photojournalism studies at San Francisco State. “Digital manipulation throws all pictures into a questionable light. It’s a gradual process of creating doubts in the viewer’s mind.”

It was precisely that concern that led National Geographic, the magazine that moved a pyramid, to rethink its position. Jan Adkins, associate art director, explains: “At the beginning of our access to Scitex, I think we were seduced by the dictum, ‘If it can be done, it must be done.’ If there was a soda can next to a bench in a contemplative park scene, we would remove the can digitally.

“But there’s a danger there. When a photograph becomes synthesis, fantasy, rather than reportage, then the whole purpose of the photograph dies. A photographer is a reporter — a photon thief, if you will. He goes and takes, with a delicate instrument, an extremely thin slice of life. When we changed that slice of life, no matter in what small way, we diluted our credibility. If images are altered to suit the editorial purposes of anyone, if soda cans or clutter or blacks or people of ethnic backgrounds are taken out, suddenly you’ve got a world that’s not only unreal but surreal.

“At National Geographic, the Scitex will never be used again to shift any one of the Seven Wonders of the World, or to delete anything that’s unpleasant or add anything that’s left out.”

Up next: Rewriting history?

Feeling reassured? Not so fast: Even if other publications begin showing similar self-restraint, digital technology is making other inroads that threaten the credibility of the photograph.

Already there are a half-dozen computer software programs on the market, such as Digital Darkroom, which allow the user to “edit” photographs digitally. The technology is still in its infancy, but the picture-altering capabilities of the million-dollar Scitex is fast moving into the hands of anyone who owns an $8,000 personal computer.

And then there is the digital camera, a sort of hand-held freeze-frame video camera that should be a hot seller in the 1990s.

What disturbs many people is that the original image exists in an electronic limbo that can be almost endlessly manipulated. That’s different from the Scitex digital retouching equipment, where there exists an original photo or negative to work from.

Nancy Tobin, art director of The Asbury Park Press, says: “This is scaring everyone, because there’s no original print, no hard copy. Talk about the ability to rewrite history!

“It literally will be possible to purge information, to alter a historic event that occurred five years ago because no original exists. There’s enormous potential for great wrong and great misuse.”

As more of these machines enter the workplace, the credibility gap for news publications is almost certain to widen. Yet nearly everyone in the field agrees on this much: It’s not the technology itself that’s the culprit.

“You’ve got to rely on people’s ethics,” says Brian Steffans, graphics editor at The Los Angeles Times. “That’s not much different from relying on the reporter’s words. You don’t cheat just because the technology is available. Machines aren’t ethical or unethical — people are.”

This article appears in “Annual Editions: Mass Media 96/97” (Third Edition). The instructors’ resource guide provides this description:

27. Photographs That Lie: The Ethical Dilemma of Digital Retouching, J. D. Lasica, American Journalism Review, June 1989.

Digital technology has made it possible to retouch photographs in almost any manner without any evidence of tampering. Retouching photographs is not new, but the sophistication and ease of digital technology make it ever more prevalent. Where do you draw the line?